Denis ‘Nick’ Nichols joined the VR in 1938, completing his elementary flying training at Sywell in Northamptonshire. On 1 September 1939, he too was called to full time service along with many other reservists, including Peter Fox and Ken Wilkinson. The threesome would go through their Service Flying Training together. Afterwards, Nick and Peter learned to fly the Hurricane, whilst Ken went to fly Spitfires. Just a fortnight later, on 15 September 1940, Sergeants Nichols and Fox, both of whom were nineteen-years-old, reported to 56 Squadron at RAF Boscombe Down in Dorset. The day afterwards, these two young fighter pilots were introduced to the grim realities of service on an operational fighter squadron when they performed duty as pall bearers at the funeral of a fellow NCO pilot who had been accidentally killed during dogfight practice.

On 30 September 1940, the Germans made their last massed formation raid in daylight. The target was the Westland Aircraft Factory at Yeovil in Somerset. Unfortunately, however, cloud obscured the target, causing a tragic navigational error: bombs cascaded not onto the intended target but on the nearby town of Sherborne in Dorset. Amongst the RAF fighters scrambled in response was 56 Squadron, and Sergeant Fox would soon catch his first glimpse of the enemy: –

‘I just couldn’t believe it. There were about forty He 111s of KG55, together with escorting Me 110s, approaching Lyme Bay, inbound. I selected one of the rearmost bombers, aimed firstly at one engine, pressed the gun button and sprayed across to the other. The enemy aircraft slowed significantly and peeled off to port. I followed, still firing, when suddenly there was an explosion and I noted that there was little left of my instrument panel! Fortunately my hood was already half open, which prevented any chance of it jamming shut in the event of the cockpit being so damaged. I broke to starboard, upwards and away, with all controls apparently functioning correctly. I got over land at 3,000 feet and was wondering whether I could make the coastal airfield at Warmwell (near Weymouth), when I saw flames coming up between my legs. I don’t think that I even thought about my next action, which was to instinctively roll the kite upside down and release my harness. I then saw my feet still above me, and the Hurricane above my feet, presumably stalled. Where was the rip chord? I told myself to calm down, and pulled the “D” ring straightaway. I had never before pulled a rip chord, never seen one pulled, never seen a parachute packed, and never had any instruction! The “D” ring was flung into the air, followed by some wire. Obviously I had broken it! I then felt the tug of the pilot chute followed almost immediately by the wrench of the main parachute. I was safe! The next second I was aware of an “enemy”, which I assumed was going to shoot me. It was, however, my flaming Hurricane, which literally missed me by inches! The kite slowly screwed round, going into a steeper and steeper dive until almost vertical, aimed directly at the cross-hedges of four fields to the Northeast of a wood towards which I was drifting. The aircraft hit the cross-hedges spot on, a short pause then a huge explosion followed by another pause before flames shot up to a great height. I’m glad that I wasn’t in it!

‘I was safe again but didn’t feel it as the sea looked rather close and I didn’t want to end up swimming. I then recalled a film about a German parachutist, which had shown how if you pulled the parachute lines on one side or the other, the direction was slipped off accordingly. I tried, but which side I don’t know as I could not see which way I was drifting. I certainly could not think aerodynamically at that moment! Leave well alone, I thought! I was safe again, then, blood! Trickling down my right leg. I tried to lift my right leg to see, but couldn’t. I’d met aircrew who had lost limbs but could still feel extremities that were no longer there. My leg must have been shot off and would crumble beneath me upon landing! I was getting close to the ground and worried about my ‘shot off’ leg when I remembered the story of a pilot being shot in the foot by the Home Guard. “BRITISH!” I shouted at the top of my voice. I pulled hard as my parachute clipped a tree on the edge of a wood. Upon landing I just fell over gently, when the wind pulled the chute sideways, and I shouted “BRITISH!” again. As no one came I started to roll up my parachute when a farm labourer climbed over a nearby fence and requested confirmation that I was okay.

‘My “shot off” leg was not, in fact, “shot off”. It was just a tiny wound on my knee where a small piece of shrapnel had entered, and another the same size also half an inch away where it had come out. A lady with a horse then came along and I draped my parachute over the animal. Off we went on foot until a van took me to Lyme Regis Police Station. I was then entertained in the local pub whilst I awaited transport back to Warmwell. Someone from Air Sea Rescue arrived and I told him that I was pretty sure that “my” Heinkel had gone into the drink.’

Peter had probably been bounced by either an Me 109 or a 110.

A week later, the Germans tried to hit Westlands again, this time with 20 Ju 88s of II/KG 51. Once more 56 Squadron joined the fray, and this time it was Sergeant Nichols’ turn to meet the enemy. At 1530 hours, Nick and four other Hurricanes were scrambled from Warmwell (from which forward airfield 56 operated on a daily basis):-

‘We took off in formation with me on the left of the leader, Flight Lieutenant Brooker, and I was “Pip-squeak” man, my radio being blocked every 15 seconds. I can’t remember hearing any R/T transmissions so perhaps the wireless was on the blink. I did not even hear the “Tally ho!”. Flying in tight formation the first I saw was tracer coming from our leader’s guns. Quick glimpse and I saw a Ju 88 and fired, still in formation, but had to break away to avoid collision with the Flight Lieutenant. I then lost the Squadron and pulled up, searching for the enemy. No sign of the bombers but 110s in a defensive spiral above. I pulled the “tit” for maximum power and went to intercept.

‘A Spitfire was attacking the top of the spiral so I went head-on for the bottom. I fired but, perhaps not surprisingly in view of their heavy forward firing armament that I must have overlooked, was hit. Flames poured from the nose of my aircraft and the windscreen was black with oil, so I broke away as I could not see out. I turned the aircraft on its back to bale out at 25,000 feet. First time a slow roll but I remained seated. Second time I tumbled out, spinning. I told myself not to panic and gave the rip chord a steady pull. When the parachute deployed, the lanyards on one side were twisted. I tried to untangle them without success but relaxed, as at about 15,000 feet I appeared to be coming down reasonably slowly. I did not see the ground ultimately rush up at me and crumpled in a heap upon landing.

‘The Home Guard then appeared on the scene and told me to stick my hands up. They thought I was German but I just laughed at them between groans as I had actually broken my back. There was a Jerry parachutist stuck up a nearby tree, from the Ju 88, but the locals refused to get him down until they had seen to me.’

Nick had landed near the village of Alton Pancras on the Dorset Downs. At about 1600 hours, Charlie Callaway, coincidentally another 19-year old, was ploughing in the ‘Vernall’ when he saw the Hurricane ‘coming down hard and well on fire!’ His younger brother Sam, 17, was rabbiting nearby and he too saw the doomed British fighter ‘descending at a shallow angle but all ablaze and travelling sharpish like. It was so close that I could have reached out and touched it. There were several parachutes in the sky at the same time’. Nick’s Hurricane, P3154, impacted at Austral Farm, some nine miles north of Dorchester.

Despite Nick’s back injury, both he and Peter were lucky: both had met the enemy on their first operational patrol; both had been shot down but they had survived.

Later, Peter Fox also broke his back whilst serving with 56 Squadron, when he was ‘flown into a haystack’. Recovered, he later went on to fly Spitfires with 234 Squadron, also out of Warmwell, until he was shot down by ground fire on October 20th, 1941, whilst crossing over the French coast near Cherbourg on a ‘Rhubarb’. Fortunately Peter made a safe forced-landing and spent the remainder of the war in captivity. Unfortunately this mishap was the last in a string of events that prevented him from being commissioned, so it was with the rank of Warrant Officer that Peter ultimately left the RAF after the war.

Nick also recovered from his broken back and went back to operational flying. Instead of single-engine fighters, however, he found himself patrolling nocturnal skies over North Africa and later the Mediterranean in a 255 Squadron Bristol Beaufighter. He was not to meet the enemy again, but was more fortunate than Peter given that Nick was commissioned in March 1942. After the war he became an airline pilot and so flew throughout his working life.

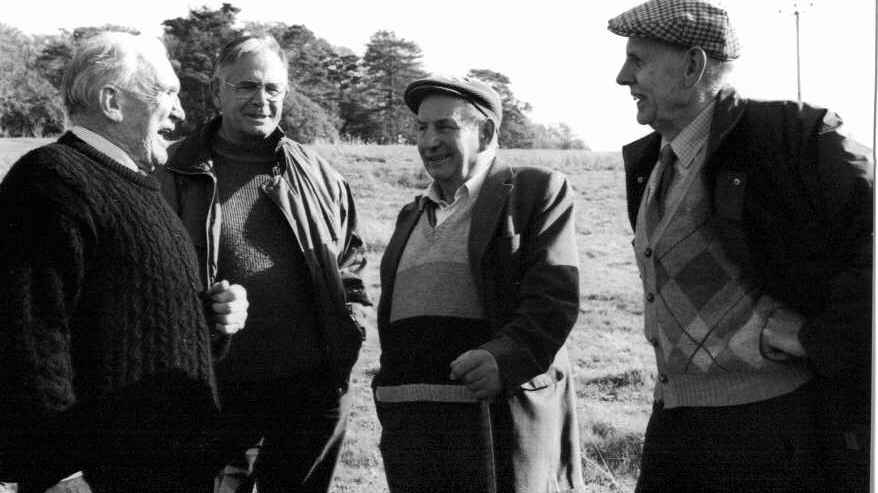

It was from talking to Nick that I first became particularly interested in the raids against Westlands. At the time I was actively involved in aviation archaeology and interested in investigating the crash site of his Hurricane. When I first explained our intention to Nick, his first reaction was “I threw it away in 1940 and I don’t want it back now!” In time, however, he became increasingly interested in the project, to the extent that he accepted our invitation to join the (former) Malvern Spitfire Team for the excavation in November 1993.

It was not until November 1995, however, that we got around to returning Peter to his Wootten Fitzpaine crash site. The remains of his N2434 (US-H) was found exactly where Peter had described it, at the cross-hedges of four fields. Although smashed to pieces, many items were found, including eyelets from Peter’s Sutton harness. At the site Peter and his wife Beryl, herself a wartime WAAF, were able to meet eyewitnesses who excitedly related their recollections, and rekindle acquaintance with our friend, former enemy fighter pilot, Hans ‘Peter’ Wulff. Once more the excavation attracted much media interest, and was broadcast as a news item the length of Britain’s south coast.

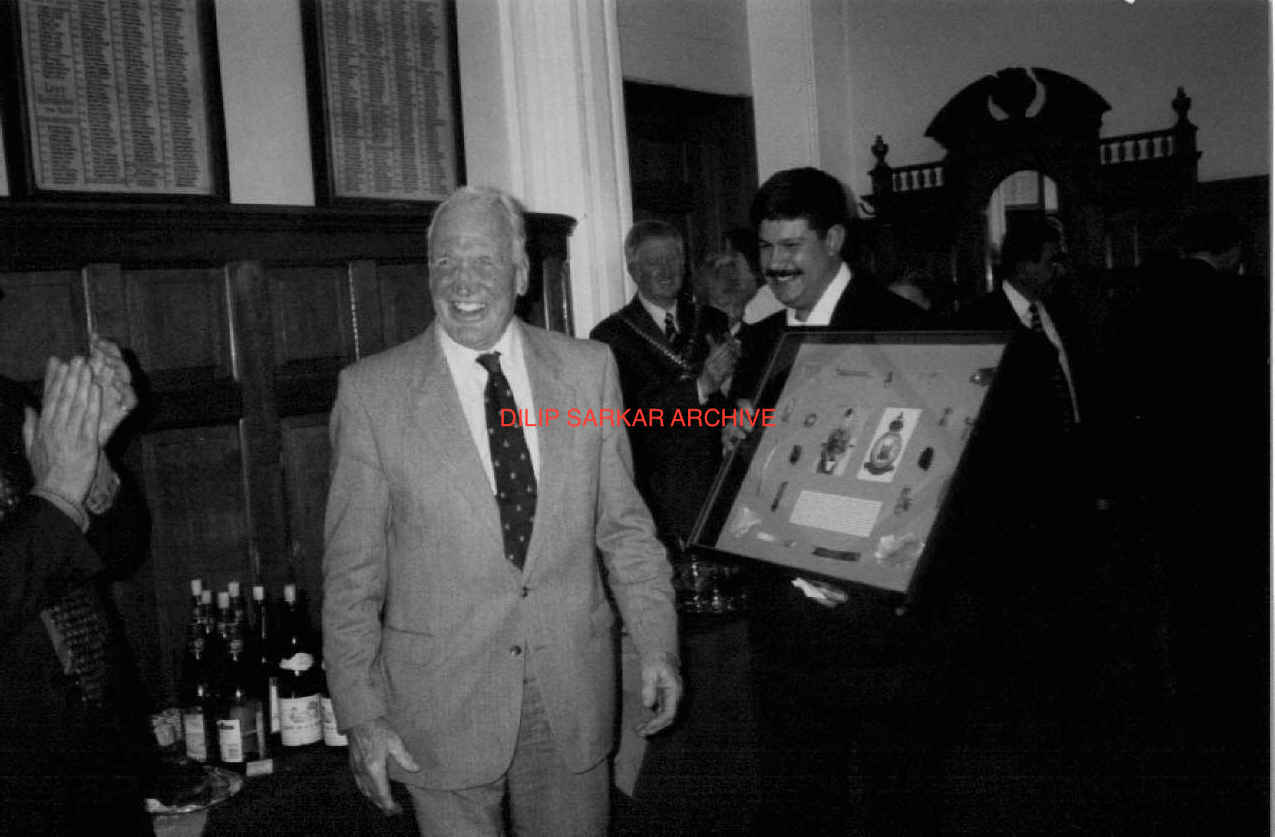

For Peter there was a bonus: having been made an honorary member of the Malvern Spitfire Team, we had applied to the MOD for ownership of N2434 to be transferred from the Crown to Peter himself. So it was that we were also able to pass Peter the official documentation confirming this to be the case, making him the only one of the Few to own his Battle of Britain aircraft!

Sadly, our German friend Hans Wulff died in 1997, since when both Denis Nichols and Peter Fox have joined him in that great hangar in the sky. I attended Peter’s funeral with Ken Wilkinson – who remarked how delighted his old friend, who had a great sense of humour, would have been when the 56 Squadron Tornado GR1, beating up the church in his honour, set off all the car alarms!

I first told the story of these bale-outs in Angriff Westland (1994), then Peter’s specific experiences were featured in A Few of the Many (1995). More recently, both Nick and Peter found currency in my Last of the Few (2010).